Though Stoicism is easy to understand, it can seem difficult at first to practice. Fortunately for us, the ancient Stoics left us with a few techniques to apply the principles of Stoicism to our daily lives. Here, we discuss a few that you can put into practice right now:

1. Create morning reminders

2. Perform negative visualization

3. Reset your goalposts

4. Practice occasional self-denial

5. Remember that life is finite

Start the day off right

Before we get into any specific techniques, however, perhaps the most important thing you can do as a Stoic is start your day with the right mindset.

That sounds easy, but if you’re anything like me, you probably wake up and immediately check your phone to respond to messages or read the news.

Once you look at your phone, it’s easy to get distracted. Your brain starts crafting that message back to your boss or gets frustrated with that politician appearing in the news. And poof, you’ve already forgotten that you’re a Stoic and the day gets away from you.

If this is you, there are two things you can do to combat your attention-sucking phone.

First, get an old-fashioned alarm clock. The alarm clock lets you wake up without reaching for your phone to turn off the alarm. Leave the phone outside your room so you can start your day in control of your own thoughts.

And second, find a way to remind yourself that you practice Stoicism!

One of the best ideas I’ve heard is from Ryan Holiday at the Daily Stoic. Ryan carries a coin with the Stoic phrase momento mori on it wherever he goes. When he puts the coin in his pocket, along with his other daily items—keys, wallet, phone—he is reminded that he is a Stoic and should practice his daily Stoic exercises.

Others get tattoos with Stoic phrases, have a bust of Seneca at their desk, or put Marcus Aurelius quotes as the background of their phone.

Personally, I subscribe to the Daily Stoic newsletter. Even if I don’t always read through the whole thing, just receiving the message in my inbox reminds me to be a Stoic for the day.

Perform negative visualization

Now that you’ve reminded yourself that you practice Stoicism, one of the most common Stoic practices is called negative visualization. Negative visualization is imagining negative circumstances to a) prepare for them and b) appreciate when they don’t happen.

Let’s look at an example.

Say you are about to fly on a plane. What are some of the things that can go wrong?

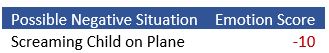

If you’re like me, you might worry that a screaming child will ruin your flight:

Negative visualization – preparation

Ask yourself, what can I do now to mitigate that problem before I get on the flight?

My time-tested solution to this problem is to download a white noise app and make sure I bring my headphones on the plane. If I find myself on a flight with a screaming child, I can pump up the white noise and, God willing, drown that screeching out.

Is that the ideal situation? No, certainly not.

But is it better than not bringing my headphones and hearing the screaming on full blast? You bet.

So that’s the first part of negative visualization: preparation. By preparing for negative circumstances that may come to pass, we can mitigate the negative emotions—irritation, frustration, annoyance—we’ll feel if they do happen after all. What’s more, our premeditation might help us feel less surprised, and therefore, less negative when the screaming child does come on the plane.

Negative visualization – appreciation

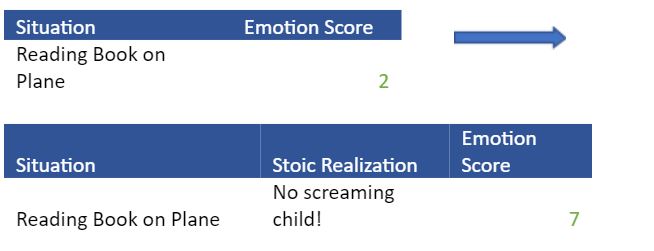

That takes us to the second part of negative visualization: appreciation.

Now picture that you’re on the plane. You’ve thought about this screaming child and how you’ll handle it if that pesky devil gets on board. As the passengers enter the plane, you don’t see any unruly children among them. So close. And just as the last passenger trickles in the cabin door shuts, you realize you’ve escaped: no screaming children.

Phew!

Because you’ve been reflecting on what can go wrong, you’ll appreciate it so much more when you can take out a good book and read on the flight without disturbances. So what might’ve been just a normal plane ride feels like a gift:

The dual purpose of negative visualization demonstrates a common misconception about Stoicism. Stoicism is not just about decreasing or eliminating our negative emotions–it’s also about increasing our positive ones. By visualizing negative circumstances, we’ll be more thankful when they don’t happen.

So when you see your Stoic reminder in the morning, run through your day quickly and try to think about what can go wrong. Maybe you’ll miss your train, or maybe your boss will be mean to you. Briefly think: how will I handle those situations? And if they don’t happen, be thankful for it!

Reset your goalposts

Negative visualization works because we, as humans, have constantly moving goalposts when it comes to our happiness.

Think of a time you were really happy about something. Maybe you got that job you’d be working to get for years. While you stayed happy a few weeks after the news, gradually that happiness started to fade. The job became the new normal. You created new goals. To be promoted. To get an award. And you’d be upset if you didn’t.

Sound familiar?

Our happiness is often relative. When we obtain something new, our new benchmark for happiness becomes the next goal, or the next thing. Our ever-moving goal post for happiness makes it hard to appreciate what we have.

Enter negative visualization.

By temporarily removing something we love from our lives, even just in our mind, we can reset our happiness goal posts.

Let’s take a more serious example.

When I practice negative visualization, I often imagine what my life would be without my wife. I think of how much I’d miss laughing together before work, going for walks, and eating dinner together. I’d miss being connected with her family and her world. And I think of how lonely I’d feel without her.

I also think of the practical things I’d lose. My wife also works, so without her I’d probably no longer be able to afford my apartment and I’d have to move further away from my job.

As the first part of negative visualization—preparation—I’d think of what I’d do without her. I’d probably leave where I live and move closer to my family to be around people. I’d probably try to surround myself with friends to get through the hard times. If the time should ever come where I’d lose her somehow, at least I’ve already thought about how to mitigate that problem, even if just a little.

But more importantly, think of the second part of negative visualization: appreciation. When I visually add my wife back into my life, it makes me so happy. I appreciate all the things—the laughter, the walks, the dinners—that I may have simply taken for granted before. I usually get up and give her a big hug after the practice, which in turn, makes our relationship even stronger.

Through negative visualization, I stop my happiness goalposts from moving further away and feel happiness for the things I already have.

Though contemplating the loss of something serious may be too heavy to do daily, consider sprinkling in a serious negative visualization exercise occasionally throughout your week to appreciate what you have.

Practice occasional self-denial

While the ancient Stoics certainly engaged in negative visualization, they also physically went without things in their life to reduce their reliance on them.

Just like negative visualization, physical denial helps us a) prepare for discomfort and b) appreciate what we have.

Encouraged by a coworker, I recently started fasting—nothing crazy, I ate meals between 12:00pm and 8:00pm instead of all day and especially late at night.

The first day I tried it, I was miserable. From 11:00am to 12:00pm I felt like I looked at the clock every minute to see when I could finally eat a peach I brought into work for a snack. I felt a little tired, a little woozy…and cranky.

When 12:00pm finally came, an ordinary peach tasted like the best thing I ever had. In fact, everything tasted better.

Over time, I realized I felt completely normal waiting to eat until 12pm. Yes, the hunger was still there, but it didn’t bother me anymore. I now just look forward to my meal, even if it is nothing particularly fancy.

I don’t fast every day anymore, but I still like to from time to time. Since then, there have been times that I’ve missed meals, and I noticed it doesn’t really bother me. The other day I went out to eat with some friends and there were unexpectedly long waits at all the restaurants in the area. While they had some “hangry” episodes, one of them actually asked me why I seemed completely calm about the situation.

Obviously, preparing ourselves ahead of time can help us weather more difficult times to come. And there are so many things we can do to prepare. We can live more frugally to prepare for poverty, exercise to prepare for physical hardship, and spend time alone to prepare for loss.

Often, life will give us unintentional opportunities to practice denial. Have you ever rushed outside without a jacket only to realize it’s colder than you thought? While that can be a frustrating situation, look at it as a chance to practice Stoicism. Try to adapt without the jacket and think of how happy you’ll feel the next day when you remember it.

Just like negative visualization, practicing (or even welcoming) physical denial can help us prepare for harder times to come and appreciate what we have in the meantime.

Remember that life is finite

Throughout this article we’ve discussed ways to prepare for negative events and appreciate what we have. Perhaps the most negative event we can prepare for is death, and the thing we can appreciate the most is life.

And so, the ancient Stoics frequently meditated on death, a practice you might hear referred to as momento mori.

It might be uncomfortable to meditate on death at first. The prospect of completely disappearing for all of eternity is well…scary.

But it’s also real. We will all die. It could happen tomorrow or 70 years from now. But it will happen to all of us.

And so just like the things we imagine not having through negative visualization and the discomfort we undergo through physical denial, we, as Stoics, also have to prepare for death and appreciate life.

In terms of preparation—if you were to die tomorrow, what are some things you are proud to have done in your life? Do more of those things while you can. What are some things you wish you did differently? Start making those changes now.

When I think back on my life, I’m proud to have made meaningful friendships—and so in preparation for death I want to maintain and continue to invest in those relationships while I still can. And when I reflect on death, I wish I spent more time appreciating the outdoors. I then like to go sit in a park and just look at the leaves and listen to the birds.

As you can already imagine, the preparation part of this exercise leads to appreciation. I’m glad I still get to see my friends, I’m glad I can go sit in nature, I’m glad I still have life and want to make the most of it.

There’s a great quote from the movie Troy that I think captures this concept well:

“The Gods envy us. They envy us because we’re mortal, because any moment might be our last. Everything is more beautiful because we’re doomed. You will never be lovelier than you are now…we will never be here again.” – Achilles in Troy (2004)

We will never be here again. And yes, I wish that weren’t the case, just as I’m sure you do. But because our lives are finite we have to make the most of every day. You won’t get a second chance to live your life—any changes you want to make, anything you want to do, you need to do now because we don’t know when our time will run out.

And that’s what is so beautiful about how Stoicism can improve our daily lives.

Not all our days here will be good ones. We will experience hardship, loss, and ultimately death. If we don’t accept and prepare for that fact, we will lose more of our precious few days to negative emotions–heartache, frustration, anger—than is necessary. And we will spend less time savoring life while we can.

Conclusion

Though we stuck with the theme of preparing for difficult events while appreciating what we have in this essay, we by no means exhausted the list of things you can do to practice Stoicism in your daily life!

Check out some of our other articles on Stoicism: