Today, we take the concept of political nationalism for granted. People with a common history, language, and culture tend to share the same government. So for instance, when we say things like ‘the French,’ ‘the Italians,’ or ‘the Chinese,’ we are referring to both the people of a geographic area that share a common culture (e.g., French food) and the political entity that serves those people (e.g., French government). Yet, this take on nationalism is fairly new. It was cultivated by French philosophers over the course of the 18th century and helped ignite the French Revolution, with dramatic results. This article explores the connection between the French Revolution and nationalism, from its origins in the writings of Rousseau to its bloody zenith in the Reign of Terror. Throughout, we focus on how nationalism encouraged France to radically redefine the relationship between its government and citizens.

Nationalism in Pre-Revolutionary Europe

Before the 18th century, the peoples of Europe navigated a maze of competing cultural and political identities. Local vs. national. Catholic vs. Protestant. Loyalty to one’s feudal lord vs. loyalty to one’s monarch. Nationalism, or the cultural bond with one’s nation, was simply one of these identities. It was neither the dominant identity nor tightly bound to any political entity. On the one hand, people united under the same government often did not see themselves as the same ‘nation.’ For instance, the sprawling Habsburg Empire included peoples as diverse as the Hungarian peasant and the Dutch merchant. On the other hand, people of the same cultural and linguistic background might be split across different governments, as was the case with the German city states and principalities.

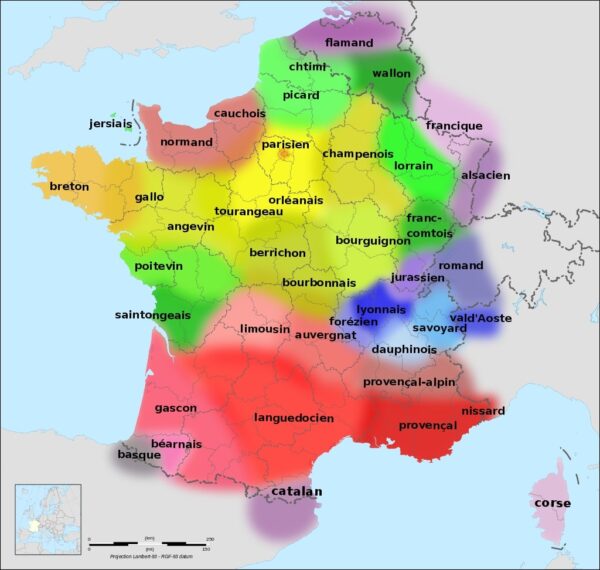

The Dialects of France: Prior to the 19th century, France was divided into groups speaking a variety of dialects. Nationalism led to a desire to unify the people and standardize the French language.[1]

Rousseau, nationalism, and popular sovereignty

In part, it took the writings of French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau to realize the potential for nationalism to serve as the bedrock for powerful states. Writing in 1762,[2] Rousseau argued that nationalism provides people with a sense of belonging, meaning, and purpose. Fostering a strong sense of nationalism in a country – an amour de la patrie, in Rousseau’s words – would allow its citizens to transcend their personal interests and work towards something greater.[3] [4] The power of nationalism to transform disparate communities into united subjects appealed to the European monarchs of the period.

In addition, Rousseau connected nationalism with popular sovereignty, allowing the budding 18th-century nationalists and liberal Enlightenment philosophers to find common cause. In The Social Contract, his magnum opus and “handbook for nation-making,” Rousseau dealt with the question of how to unite the people of a nation and their government.[5] The treatise’s thesis proposed that citizens of a nation can only thrive by participating in politics and thus expressing the “general will.”[6] The role of the sovereign was to encourage the citizenry’s participation in government and ensure the people’s will was carried out.[7] In return for the sovereign’s guarantee to express the general will, the people would serve the sovereign, and the nation at large, with patriotism and virtue.

In Rousseau’s mind, then, nationalism was the key to securing both liberty for the people and loyalty to the state. This idea would go on to change all of Europe.

Nationalism and the start of the French Revolution

Nationalism gains strength before the French Revolution

In France, nationalism played a large role in driving the country to and eventually shaping its Revolution. Faced with mounting debt and growing discontent, King Louis XVI turned to nationalism to rally the country.[8] In addressing the Assembly of Nobles, the king’s director of fiscal policy notably replaced the traditional maxim of “as the King wishes, so it be law” to “as the happiness of the people commands, so the King desires,” a clear reflection of Rousseau’s concept of popular sovereignty.[9]

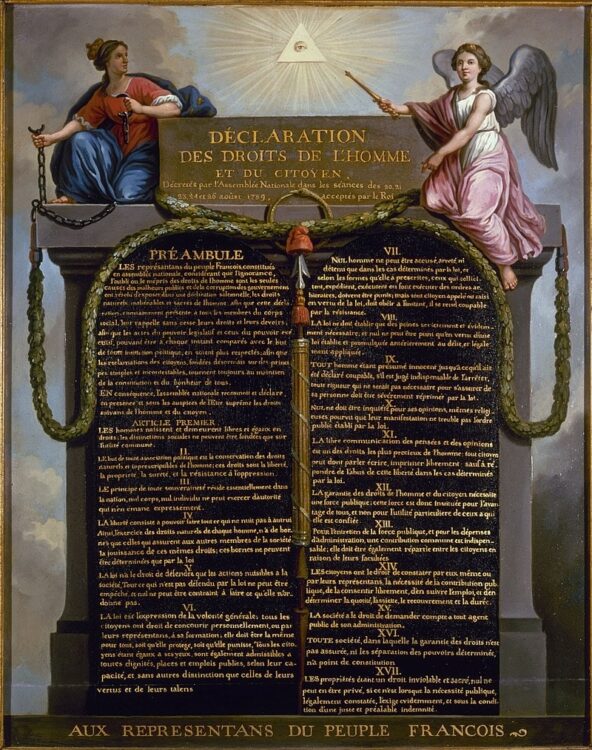

In France’s legislative body, the Estates-General, an outpouring of nationalist sentiment led to significant changes in the distribution of power. The Third Estate (representing the commoners) argued that the nobility and the clergy were “burdens upon the nation” that “chain[ed]” the will of the people.[10] So, they abolished feudal privileges and promulgated the Declaration of the Rights of Man. Seeking to uphold the human rights of all citizens, the Declaration reads as if it were written by Rousseau. For instance, Article Three states “The principle of all sovereignty lies in the nation” while Article Six adds that “The Law is the expression of the general will.”[11] In these pre-Revolutionary days, nationalistic ideology pushed France to unify around the banner of popular sovereignty to face the country’s financial difficulties.

Nationalism sparks revolution in France

And yet, the people did not respond to their newfound popular sovereignty by loyally supporting their sovereign. New leaders stoked the growing fervor to mobilize the French people and implement a series of radical measures. The National Guard soon led a popular takeover of the Tuileries Palace, driving the king further into hiding. Then, mere weeks later, the monarchy was officially abolished, erasing any doubts of the Revolution’s significance.[12]

But, this was not the most radical action taken. From September 2nd to 6th, violently nationalistic crowds thundered through the prisons of Paris, capturing inmates, trying them before makeshift courts, and executing well over 1000 of them. They justified this as an attempt to purge la patrie of immorality and safeguard their homeland. Rousseau’s nationalism, initially used simply to unite the country, had now taken a turn. The general will became fanatical and the common. Uniting experiences became riots and executions.[13],[14]

On January 21, 1793, King Louis XVI approached the guillotine. And, when his bloody head was hoisted before the cheering crowds of Frenchmen below, the customary declaration of “the king is dead, long live the king” was ousted by the revolutionary cry of “Vive la nation!” Thus, the rabid throngs of Paris hailed a new era.[15] The moment’s symbolism was clear: the state had supplanted the king. It was the authority, and it followed the Rousseauian rubric of deriving its power from the people. The connection between the French Revolution and nationalism had mutated. The state executed nearly 40,000 people between the summers of 1793 and ’94.[16]

Conclusion

Over the course of just a decade, the French people experienced lofty highs and bloody lows of nationalism. Awakening a sense of unity in a country previously defined by its monarchy, nationalism propelled average citizens to the forefront of a nation long-dominated by noble families and clergymen. It promulgated the protection of human rights as the core government function. Also, it eventually harnessed the full potential of French manpower to defeat the other major European powers. Yet, those motivated by a sense of community were susceptible to a hatred of their fellow citizens. Those that promulgated the Declaration of the Rights of Man held show trials and mass executions. And those that deposed a king consolidated behind Napoleon. As we consider the impact of nationalism and self-determination in today’s society, it is important to keep these contradictions in mind.

References

[1] Langues de la France1.gif: Taken from Lexilogos.com with permission from the copyright holder: “oui pour wikipedia! je vous demanderais de préciser la source en plaçant un lien vers cette page”Départements de France-simple.svg: SuperManuFile:France map Lambert-93 with regions and departments-blank.svg: Eric Gaba (Sting – fr:Sting)derivative work: Hellotheworld, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

[2] Derek Hastings, Nationalism in Modern Europe: Politics, Identity, and Belonging since the French Revolution (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2018), 14.

[3] Steven T. Engel, “Rousseau and Imagined Communities,” The Review of Politics 67, no. 3 (2005): 534, www.jstor.org/stable/25046445.

[4] Timothy Tackett, The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of the Harvard University Press, 2015), 68.

[5] Robert R. Palmer, “The National Idea in France before the Revolution,” Journal of the History of Ideas 1, no. 1 (1940): 106, www.jstor.org/stable/2707012.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Hastings, Modern Europe, 22.

[9] Ibid, 23.

[10] Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, What is the Third Estate? (Paris: 1789; University of Oregon), pages.uoregon.edu /dluebke/301ModernEurope/Sieyes3dEstate.pdf.

[11] Marquis de Lafayette and Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès, “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” (Paris: 1789; Yale Avalon Project: 2008).

[12] Hastings, Modern Europe, 27..

[13] Ibid.

[14] Engel, “Imagine Communities,” 531.

[15] Hastings, Modern Europe, 30.

[16] Ibid., 31.