At first glance, it may seem like the gladiator games in Ancient Rome made Romans of all classes equal. The spectacle of men fighting attracted Romans from all walks of life. Senators and commoners, rich and poor, men and women rubbed elbows together in the arena. In the imperial period, a commoner might even see the Emperor himself at the games, cheering like one of the plebs.

But, perhaps it is wrong to view gladiator games as events where Romans were unified by their love of violence, politics took time off, and social differences between classes were temporarily forgotten. For, in reality, the games represented a complex transaction between the Roman elites sponsoring the games and the commoners attending them. In fact, the games were permeated by politics and social status, affecting everything from the seating arrangements to the type of combatants.

Examining The Role of Gladiator Games in Ancient Rome

In this article, we survey the role of the games in Rome by examining the nature of this ‘transaction’ between the Roman elites and the commoners. What did each class stand to gain from putting on or attending the games? In what way were the games used to manipulate and control Roman society by those in power?

To answer these questions, we first discuss how the gladiatorial games became a kind of patron-client gift-exchange during the Republic. Then, we look at how elites benefited from hosting the games. Next, we study why the games were so popular with the Roman people. Finally, we examine how under the Empire, the games were regulated to solidify the Emperor’s social control over the people.

The Importance of Patronage in Roman Society

Let’s begin by looking at how gladiatorial shows during the Late Republic were a ‘transaction’ between the elites and the common people. To do this, we must first discuss patronage and its importance in Roman society.

Patronage Defined

Defined simply, patronage is a system of favors between a person in power (the “patron”) and a person of lower status (the “client”). When you hear the word ‘patronage,’ think The Godfather. Mob boss Vito Corleone is a perfect example of a modern-day patron. As a powerful figure, he intervenes in various issues on behalf of his Italian immigrant community. He punishes a group of teenagers that attacked the mortician’s daughter. His associates intimidate the head of a movie studio into giving his godson a part in a film. In return, his clients repay their favors: the mortician later provides funeral services for Vito’s family while his godson agrees to perform at the Coreleone family’s casino.

Note that a patronage exchange is much different from a standard ‘economic’ exchange. When I buy a pair of pants for instance, I hand the cashier money and he hands me the pants. That’s it. In contrast, a patron exchange is unwritten, long-lasting, and often non-monetary. It’s based on favors, not dollars and cents.

Patronage in Roman Society

While we don’t usually use (or admit to using) patronage today, the Romans engaged in patronage as standard practice. A typical Roman patron-client relationship might consist of a noble providing legal advice to a commoner, agreeing to intervene with the Roman government on his client’s behalf, or even providing loans to his client.[1] In return, the client would increase the patron’s authority by greeting the patron at his house in the morning, going with him to the forum (entourage!), or supporting the patron in elections and military campaigns.[2]

Patron-client relationships were acknowledged openly and clients routinely fulfilled their obligations to their patrons. In the Second Punic War, for instance, the influential Scipio family formed an army to invade Spain with many volunteers drawn from their client base.[3] On the whole, the ‘exchange’ taking place between the members of the Roman elite and the common people is clear: the wealthy or influential patron provides the client with an otherwise inaccessible good, while the client agrees to support the patron publicly and even militarily, thereby enhancing the patron’s power and prestige.

The Gladiator Games as Large-Scale Patronage

Keeping this in mind, gladiator games were a form of patronage adapted to courting Rome’s growing population. In Rome’s early days, patron relationships were conducted on an individual to individual basis. But, the number of Roman citizens ballooned during the middle and late republic to around 250,000 people. It was “simply too numerous to enter into significant personal relations with the few hundred members of the political elite.”[4] A patron could no longer acquire significant political or social authority by providing services on an individual basis. There was a need to win over the commoners on a larger scale.

The Emergence of Lavish Gladiator Games in Ancient Rome

Enter the gladiatorial games, which provided the nobility a perfect opportunity for this “mass” patronage. First, like providing legal advice or government access, sponsoring the gladiatorial games was traditionally the privilege of wealthy members of the elite rather than the state, religious authorities, or lesser members of the nobility.

Gladiator Games as Funeral Ceremonies

As explained by Roman writers Livy and Servius, gladiatorial games were originally held as part of the funeral ceremonies for powerful men,[5] [6] a responsibility that often fell to private individuals. This custom ensured that the games would be directly associated with their sponsors. In fact, writing over one hundred years after the events,[7] Livy still specifically mentions the men who gave gladiatorial shows—Decimus Junius Brutus in 264 BC, the sons of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in 216 BC,[8] and Quintus Fulvius in 179 BC.[9] Even if Livy does not refer to actual historical events, his desire to associate shows with patrons likely supports the general Roman tendency to do the same. With the gladiatorial shows so intertwined with their hosts, the populace would know exactly who to “support” in exchange for seeing the show.

Gladiator Games as a Socially Acceptable Way of Showing Off

Second, the traditional belief that the games honored the deceased provided a convenient excuse for the patron to produce lavish spectacles for the whole populace (clearly designed to enhance his own status) without directly arousing Roman hostility towards excessive ambition.

Livy attests that funeral games were extravagant public spectacles from the start. Brutus and Lepidus’ sons held their games in the city’s Forum for public viewing. This is the modern equivalent of hosting a private celebration in Times Square. The games honoring Lepidus took three whole days, while at Licinius’ games, meat was given to the population.[10] Hence, later in the Republic, when Julius Caesar displayed three hundred and twenty pairs of gladiators to “put people in such a humor… [to give him] new offices and new honors,” he could at least justify his extravagance by claiming that the games really honored his daughter Julia, although she was long since dead.[11]

In essence, gladiatorial shows were restricted ‘patronal goods’ that nobles gave to commoners, in a manner sanctioned by Roman tradition.

The Benefits Received by Elites for Hosting Gladiator Games

But did it work? Did the people actually support the patron’s “power and prestige” if he hosted games?

It seems so.

Gladiator Games as a Road to Public Office

Sources indicate that sponsoring gladiatorial shows led directly to increased status and influence for the patron. Dio Cassius reports, in business-like fashion, that Statilius Taurus obtained the privilege of “choosing one of the praetors each year” because (our emphasis) he constructed a stone arena for viewing the games in Rome.[12]

On the whole, the patronal exchange is clear. Commoners openly exchanged their votes in elections for games provided by patrons. Similarly, Plutarch’s description of Caesar’s games (quoted above), indicates a causal connection between Caesar’s largesse and the public’s willingness to heap new offices and honors upon him. Officials ranging from town mayors to the Emperor Augustus commemorated their games with stone inscriptions. Clearly, they felt that hosting gladiator games would increase their prestige in the eyes of future generations.

Gladiator Games as a Dangerous Influence

In fact, the people were so willing to support a patron of the games that some thought the practice was becoming dangerous. A law proposed by Cicero demonstrates that Roman authorities—elites themselves—became uneasy with the influence one got from gladiators. It prohibits anyone from exhibiting shows of gladiators within two years of having stood, or being about to stand, for any office.[13] Here, it is striking that the Romans believed the games could influence election results over such a long period (two years). Also, it seems that the games could increase the reputation of someone already in power to an unsafe level.

Perhaps, from a similar concern, Nero banned magistrates and procurators from “exhibit[ing] a show of gladiators” in the provinces.[14] While the author Tacitus suggests that provincial magistrates used the games to extort money from the people, it seems possible, given the analysis above, that Nero really wanted to prevent magistrates from creating spheres of influence in the provinces that could challenge his power in Rome.

In summary, the evidence demonstrates that gladiatorial games did function like patronage. A noble could expect to receive political influence in exchange for putting on gladiatorial shows.

“The emperor [Nero] by an edict forbade any magistrate or procurator in the government of a province to exhibit a show of gladiators, or of wild beasts, or indeed any other public entertainment…”

Tacitus, Annals 13.31

The Romans’ Enthusiasm for Gladiator Games

It may seem strange that the common people were so easily swayed by gladiatorial spectacles. They quite literally handed over their political support to the highest bidder. Some Roman commentators expressed the same disbelief, too. The satirist Juvenal dismally notes that once Roman masses “lost their votes” and their ability to grant “powers,” “office[s],” and “legions,” they became concerned with “bread and circuses”[15] and little else. While elites like Juvenal might scoff at commoners, he doesn’t seem to exaggerate the popularity of the games. Tacitus notes 50,000 spectators—the size of a small city— attended the games at Fidenae, causing the amphitheater to collapse.[16]

The Romans’ Obsession with Gladiators

Men and women alike obsessed over individual gladiators. For women, the obsession seems to have been sexual, at least from the perspective of moralizing male writers. Tertullian mentions that noble women commonly “[gave] their bodies”[17] to gladiators. Juvenal attributes this to the fact that women “love the steel.”[18] Men were equally enamored, depicting gladiators in graffiti, recording match results, and even writing odes to their favorites.[19]

Depictions of gladiators were even in the home. Domestic paintings in Pompeii featured gladiators, with idealized bodies, engaged in bloody combat with each other or wild beasts.[20] Some Romans went so far as to believe that gladiators had magical powers. Pliny writes that epileptics actually drank gladiator’s blood as an elixir.[21] A Roman encyclopedia suggests combing a maiden’s hair with a spear that pierced a gladiator’s side would bring fertility to her marriage.[22]

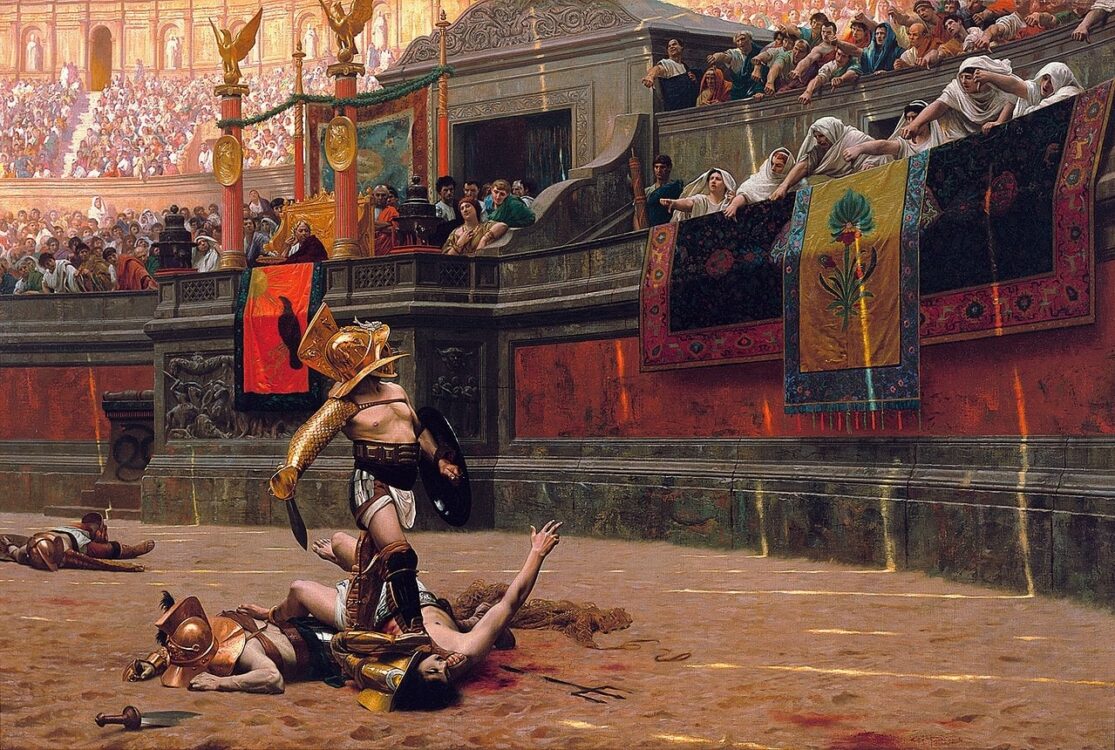

The Excitement of Gladiator Games in Ancient Rome

So, what was the root of this obsession? On the one hand, the games themselves must have been riveting. The prospect of seeing live combat and exotic animals, hearing the clash of steel and the roar of the crowd, and experiencing the energy of a game-day atmosphere had to have been genuinely exciting for a common Roman, who might have spent his typical day minding a food stall[23] or laying bricks.

Images of the Games

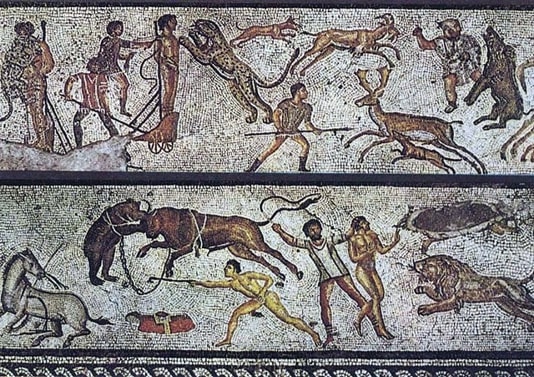

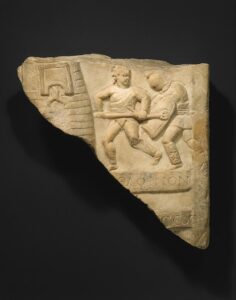

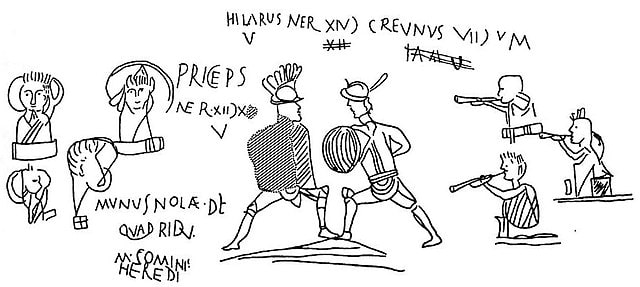

That the Romans loved the “live-action” of the games is evident in their paintings and graffiti. Both favor bloody, mid-combat depictions of their gladiators over stoic poses (like those found on equestrian statues). One painting emphasizes the excitement of the games by illustrating a gladiator knocked mid-air with his shield flying out of his hand (below left), allowing the implied gravity to create a sense of physical motion in the painting.

Other images create an illusion of motion by showing the contraction of a gladiator’s muscles. A painting of a Retiarius stabbing a netted opponent, for example, uses the bulging calf muscle and raised heel of his left leg to express the thrust of the spear (below middle) to the viewer. But, Roman reliefs might illustrate the chaos of the gladiatorial games best. Altogether, these three dimensional carvings of contorted bodies, flailing limbs, and ferocious lions capture all the pandemonium of a bar-room-brawl mixed with a safari-gone-horribly-wrong (below right).

The Importance of Sound

One other aspect of gladiatorial imagery deserves attention: the role of sound, which, like motion, the Romans sometimes go to great lengths to recreate in a static image. The Zliten Mosaic portrays the musicians accompanying the games blowing on their horns and flutes[24] as does a piece of graffiti. Roman artists also represent sound using the open mouths of the combatants, the animals, and the referees of the match, which likely indicate screams, roars, and shouts, respectively. When analyzed together with the emphasis on motion, it becomes clear that the Roman artists are not just trying to “represent” the games. In truth, they are trying to “recreate” the atmosphere of the arena—the same movements and roars—for the viewer.

The Commoners as ‘Patrons’ of Gladiators

Despite the Romans’ passion for the sights and sounds of the arena, politics and society made the games’ popular, too. In particular, the relationship between gladiators and their Roman supporters suggests that the gladiatorial games served as a kind of compensation for the politically disempowered masses of the late Republic[26] and Empire. In essence, the games gave citizens a chance to exert their status over lesser members of Roman society.

The Low Social Status of Gladiators

Although Romans idolized gladiators, they treated those who fought in the games as lower class citizens by law and custom. Roman laws banned gladiators from holding municipal office, becoming Senators or equestrians, and from receiving certain honors. The Christian writer Tertullian states that gladiators were treated with social “ignominy.”[27] Additionally, the law banning gladiators from municipal office seems to equate gladiators with prostitutes and pimps.

So, how can one reconcile gladiators popular glorification and social degradation? On the surface, maybe, increasing the status of a lower-class citizen made the position of the commoners look better. If a gladiator were “the pride of the age in martial contests,” one who “walks proudly with warlike spear,” as Martial writes of the gladiator Hermes,[28] how much greater were the commoners who possessed all the privileges of citizens the gladiator did not? That the status of the gladiators reflected the Roman people’s standing might explain two divergent depictions of the gladiator found in the muscled, god-like, combatants in paintings and the horribly disfigured gladiator described by Juvenal.[29] The painters want to flatter their Roman customers. In contrast, the jaded satirist wanted to tease the people who idolized what were, in essence, horribly mistreated slaves.

Specific Commoners Supported Specific Gladiators

The status distinction between gladiators and the common people was even more precise. Romans tended to not only idealize gladiators generally, but specific Romans supported specific gladiators. Graffiti from Pompeii indicates that Pompeians supported M. Attilius. Other cities and individuals supported categories of armored gladiators.[30] In other words, a lower-class gladiator would be specifically tied to higher-class members of the commons.

Note the similarity between the commoner-gladiator relationship and the patron-client relationship. Commoners could “intercede” on behalf of a popular gladiator with the Emperor by pleading for the gladiator’s life with hand signals, much like a patron would intercede on behalf of a client. In return, the gladiator repaid his supporters by winning matches or fighting honorably, thereby increasing his “patron’s” prestige.[31]

Rivalries broke out among the people, much like the infighting that occurred among members of the nobility. The Pompeians actually killed members of the “rival” town Nuceria.[32] In fact, Nero had to ban certain fights because the people had become so divided among themselves that they threatened “grave commotions” for the state.[33] In this sense then, the gladiatorial games were more than just exciting fights. They gave a disempowered populace a chance to play patron for a day, rewarding their clients and fighting among each other. Perhaps the best evidence of this comes from the Emperor Claudius, who acknowledging the role-reversal of the “fake” society created by the games, commonly joked that the people were the “masters” in the arena.[34]

The Elimination of Gladiator-based Patronage by the Empire

So far, we have made two observations about gladiator combat in Rome, both of which center around patronage. First, gladiator games served as a kind of patronage between the Roman elites and the common people. Second, gladiator games created a kind of fictional society. In this society, the common people acted as patrons towards the lower-class gladiators. Therefore, we conclude by examining how the emperors, the “patrons” of Rome, regulated the games to consolidate authority.

Emperors Restrict Individuals from Hosting Games

On the one hand, the Emperors curtailed the ability of individual citizens to put on games. Augustus ordered that festivals only be funded through the public treasury, prohibited individual praetors from outspending each other on gladiatorial games, and even went so far as to limit the number of gladiators involved.[35]

The effects of this legislation are twofold. First, by publicly funding the games, Augustus broke the patronal relationship between the commoners and the elites and funneled it to himself (the head of the public treasury), instead. Second, by preventing lavish spending and limiting the games’ size, he ensured that no individual could challenge his authority. Furthermore, other emperors passed similar decrees. For example, Nero banned provincial magistrates from holding games,[36] while Tacitus suggests that Tiberius might have banned the games altogether.[37] In each case, the emperors believed that allowing the elites and commoners to interact through the games threatened their authority. Hence, this clearly supports the contention that the games functioned as a political good.

Emperors Regulate the Fictional Society of the Arena

On the other hand, the emperors showed a keen interest in regulating the “pretend” society created during the games. While the commoners were still allowed to support their favorite fighters and appeal to the emperor, the emperors, particularly Augustus, checked the power that the commons had in the arena. Augustus imposed seating regulations based on status, separating women and men, Senators and commoners, and holy people and lay.[38] This attention to the seating arrangements also allowed the Emperors to reward “honorable” people, like war-heroes or other noblemen.

Again, the emperors’ reforms in the arena have two purposes. First, the Emperor breaks the power that the commons had in the arena by visibly re-imposing the normal societal class structure in the seating arrangements. Second, the Emperor consolidates the arena society through himself, by giving himself the ability to reward good and bad citizens through the seating arrangements.

Conclusion

The Emperor’s suspicion of both the elites and the common people shows that the gladiatorial games were a great source of power in Roman society. On the surface, the brutal combat demonstrated Roman power; its dominance over the lower-class gladiators condemned to a life of fighting. But in reality, the games served as a battleground for members of the elite, fighting to obtain power and the support of the common people. The gladiatorial games then, might best be thought of as the physical manifestation of the “combat” between the various classes in Roman society constantly engaged in a chaotic, but strategic fight for control of Rome.

Interested in Ancient Rome? Check out our article on Hannibal and the Second Punic War.

References

References – The Importance of Patronage in Roman Society

[1] Andew Wallace-Hadrill, Patronage in Ancient Society (New York: Routledge, 1989) 72.

[2] N.S. Gill “Ancient Roman History: Salutatio” ThoughtCo, Aug. 26, 2020, https://www.thoughtco.com/ancient-roman-history-salutatio-112667

[3] David Potter, Ancient Rome: A New History (New York: Thames and Hudson, 2009), 69.

References – The Gladiator Games as Large Scale Patronage

[4] Wallace-Hadrill, 69.

[5] Livy, History of Rome, Books VIII-X With an English Translation, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1926), Book 16 Summary

[6] Servius, Servii Grammatici in Vergilii Aeneidos, 3.67.

[7] “Livy,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/344974/Livy

[8] Livy, Book 23, 30.16

[9] Livy, Book 40, 44.8-12.

[10] Livy, Book 39, 46.2

[11] Plutarch, Plutarch’s Lives with an English Translation by Bernadotte Perrin (Cambridge, Harvard University Press 1919) 5.5

[12] Cassius Dio, Roman History (Loeb Classical Library, 1917), Book 51.23

[13] Cicero, The Orations of Marcus Tullius Cicero, literally Translated by C.D. Yonge (London: George Bell & Sons, 1891), In Vatinium 37

[14] Tacitus, Annals (New York: Random House, 1942), 13.31

References – The Romans’ Enthusiasm for Gladiator Games

[15] Juvenal, Satire X, 55-140

[16] Tacitus, Annals 4.62

[17] Tertullian, De spectaculis, 22

[18] Juvenal, Satire VI 82-113

[19] Martial, Epigrams I.29

[20] “The Roman Gladiator,” Essays on the History and Culture of Rome, The University of Chicago. http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/gladiators.html

[21] Pliny, Natural History, 28.4

[22] Festus, 55 L, caelibari hasta

[23] Alcock, Food Preparation and Food Professions, 126.

[24] “The Zliten Mosiac,” Essays on the History and Culture of Rome, The University of Chicago, http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/gladiators/zliten.html

[25] Carole Raddato from FRANKFURT, Germany, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

References – The Commoners as Patrons of Gladiators

[26] See above for discussion of population growth under the Republic.

[27] Tertullian, De spectaculis, 22 for preceding discussion on the social status of gladiators

[28] Martial, Epigrams V.24

[29] Juvenal, Satire VI 82-113

[30] “The Roman Gladiator” contextualizes both images.

[31] Something similar occurs in modern sports today when the city of a victorious team holds a “victory” parade.

[32] Tacitus, Annals 14.17

[33] Ibid

[34] Suetonius, The Lives of the Twelve Caesars: The Life of Claudius, 21

References – The Elimination of Gladiator-based Patronage by the Empire

[35] Cassius Dio, Roman History 54.2

[36] Tacitus, Annals 13.31

[37] Tacitus, Annals 4.62

[38] Suetonius, The Life of Augustus 44