Have you ever heard of the Tiwanaku Empire or why it collapsed?

We hadn’t. And we weren’t alone. When European colonizers first arrived in South America just 400 years after the empire’s collapse, none of the indigenous people knew who had built the magnificent buildings at Tiwanaku or what had happened to them.[i]

Thanks to modern archaeology, however, the academic world knows more about the Tiwanaku and can speculate on what may have led to their disappearance.

Overview of the Tiwanaku Empire

Arising on the southern shores of Lake Titicaca in modern day Bolivia, the Tiwanaku Empire thrived from 100 AD to around 1000 AD. Sophisticated builders, famers, and traders, the Tiwanaku extended their influence over portions of the South American coast. It may have even shared cultural practices with the Incan Empire encountered by Spanish explorers centuries later. Today, one can see monumental ruins of the empire’s capital, also called Tiwanaku, which once housed up to 20,000 people.[ii]

The Tiwanaku economy

While the Tiwanaku people did not leave written records, archaeologists have uncovered much about their economic life. Living in an elevated region in the Andes Mountains near Lake Titicaca, the Tiwanaku people relied on a mix of agriculture, pastoralism, fishing, and trade to meet their needs.

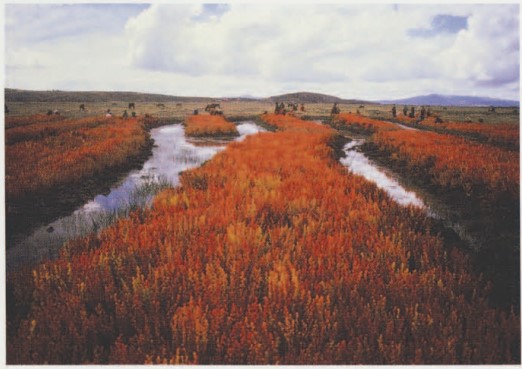

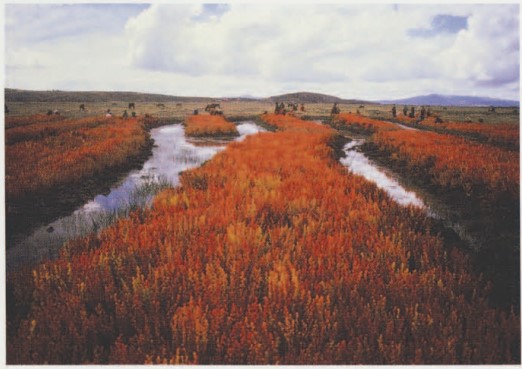

From an agriculture perspective, Tiwanaku farmers developed a sophisticated system of land management called “raised fields” or suka qullu, which complemented more traditional forms of irrigation and terraced farming. In suka qullu, crops were planted on mounds of soil surrounded by channels of water, which nourished the crops and kept them warm at night by absorbing sunlight during the day, preventing frost. In fact, some modern experiments have shown that the suka qullu system rivalled modern farming techniques for some crops grown in the Andes’ region.[iii]

Furthermore, the Tiwanaku people raised animals, the most important of which were llamas and their cousins, alpacas. While both animals provided a source of meat, they primarily served as pack animals, carrying heavy loads up and down mountainous terrain and ferrying trade between Tiwanaku and other settlements.

Excavations found evidence that the Tiwanaku people obtained cocoa, precious metals, and bird feathers from other settlements throughout South America. In fact, scholars believe the Tiwanaku state organized trade caravans of llamas to ensure a steady flow of trade goods.[v]

Tiwanaku culture

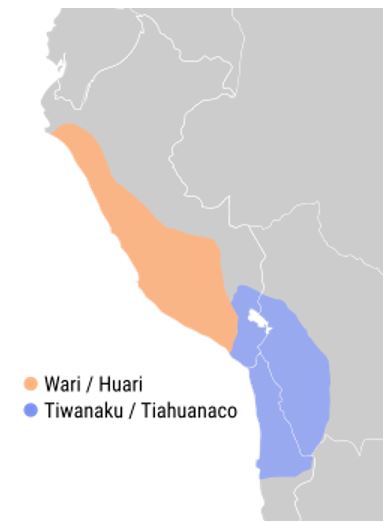

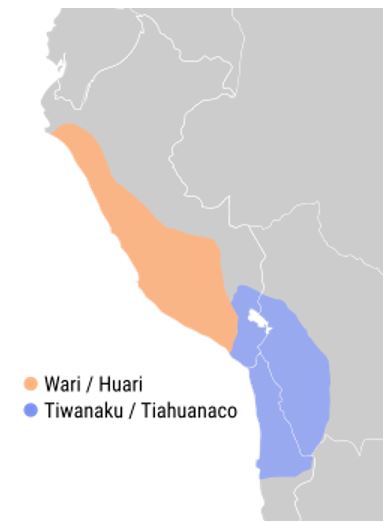

Much of what we know about Tiwanaku culture comes from archaeological findings in the Empire’s capital city and by comparisons to the Wari / Huari culture to the north. The Tiwanaku had a rich religious life. For example, a large stone pyramid found in the capital was likely a temple to one or many gods. In it, throngs of worshippers could gather for religious festivals. The discovery of mutilated corpses around this temple complex suggests that the Tiwanaku may have practiced human sacrifice, most likely of enemies captured in battle or foreigners.[vii]

The ruins of Tiwanaku indicate that the people that lived there were gifted artists. Most of their artwork likely had religious significance. For instance, The Gateway of the Sun, a large stone monolith found by European explorers at the site, may have been related to solar worship.[viii]

Other artifacts, such as the statue depicted in Figure 6 below, were likely commissioned by elite families to serve as stylized portraits. The statue is holding what scholars think are snuff boxes, possibly a symbol of high social status. Its richly patterned skirt may have exemplified what the upper classes wore for important occasions.[ix]

Why did the Tiwanaku Empire collapse?

Archaeological evidence suggests that the Tiwanaku civilization disappeared by 1150 AD. How could such a thriving society suddenly vanish?[x]

Climate and the Tiwanaku Empire’s collapse

One reason is climate. Climate historians have found evidence that the Lake Titicaca region suffered a severe decline in rainfall around 1100 AD. The shoreline of Lake Titicaca retreated by several kilometers. Local water tables receded deeper into the earth. The impact on Tiwanaku’s agriculture was devastating. In addition to declines in crop yields, shifts in waterways required the re-routing of canals and the re-planting of crops. Such disruption likely weakened the Tiwanaku society, making it vulnerable to famine, internal strife, and outside invasion.

Immigration and the Tiwanaku Empire’s collapse

Another possible explanation for Tiwanaku’s collapse is the rising power of the Aymara ethnic group, which migrated from Peru into the Tiwanaku region south of Lake Titicaca. Scholars that support this explanation believe that the Aymara culture, either through conquest or influence, gradually supplanted the Tiwanaku culture. As power shifted from the existing Tiwanaku culture to the new arrivals from the north, Tiwanaku religious, government, and social structures eroded, leading the society to be absorbed by the Aymara culture.

Tiwanaku’s collapse was not sudden

Regardless of the explanation, one thing that scholars tend to agree on is that the Tiwanaku did not vanish suddenly. Despite the drought and the potential violence accompanying Aymara immigration, the archaeological evidence suggests that Tiwanaku’s settlements were abandoned slowly. Outlying buildings were abandoned before ones closer to the city center. When larger buildings were vacated, smaller buildings were built in their place. Newer buildings might even have reused stone from monumental temples and other structures.

In summary, a combination of environmental and socio-political factors caused a gradual abandonment of Tiwanaku culture around 1100 AD. On the one hand, drought decreased agricultural yields, leading to a decline in population. On the other hand, the migration of a new people also shifted political and religious weight to north Lake Titicaca. It was the combination of these two factors that led to the final decline of the Tiwanaku civilization.

References

[i] John Wayne Janusek, Identity and Power in the Ancient Andes: Tiwanaku Cities through Time, Taylor & Francis Group (2004), p. XVI.

[ii] Ibid, XVII for dates.

[iii] Clark L. Erikson, “Raised Field Agriculture in the Lake Titicaca Basin,” Expedition, Vol. 30, No. 3., https://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/30-3/Raised.pdf

[iv] “Raised Field Agriculture in the Lake Titicaca Basin”

[v] K. Kris Hirst, “Tiwanaku Empire – Ancient City and Imperial State in South America,” ThoughtCo., December 2020. https://www.thoughtco.com/tiwanaku-empire-timeline-173045#:~:text=Trade%20and%20Exchange,-After%20about%20500&text=The%20system%20was%20connected%20back,birds%2C%20hallucinogens%2C%20and%20hardwoods.

[vi] Andean Lodges, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Un_pastoreo_con_sus_llamas.jpg

[vii] Baker, Benson, and Hermsen, “Tiwanaku Culture,” Early Civilizations in the Americas Reference Library, Gale (2005).

[viii] Ibid.

[ix] “Figure with Ceremonial Objects,” The Met, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/313010.

[x] Identity and Power in the Ancient Andes, see Chapter 9 starting on page 249 for full discussion.